MONSTERS PERVADE CINEMA

That monsters pervade cinema is clear. From their earlier incarnations – Wegener’s Golum (1915), Melies’ mummified Cleopatra in Robbing Cleopatra’s Tomb (1899) – to their revisionist ancestors in Guillermo Del Toro’s body of work (2006’s Pan’s Labyrinth, 2008’s Hellboy 2: The Golden Army, 2017’s The Shape of Water) filmic horrors have had an enduring connection with collective cultural zeitgeists. We know the iconic representations of cinematic monsters as well as we know the back of our hands: properties like Toho Co. Ltd’s Godzilla, Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein and RKO’s King Kong have left an indelible imprint on our broader pop cultural consciousness.

The Spanish romantic Goya once wrote, in the notes for his aquatint The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799): ‘When abandoned by Reason, Imagination produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their wonders,’ (Gamwell 2000:78). Predating the advent of cinema by almost a century, the notion articulates the tangled relationship that the formation of monsters has with sleep, imagination and wonder. Is it such a stretch then to comprehend why film, a medium that has been so oft correlated with the process of dreaming (Sharot 2015), might hold such a keen fascination for the monster? Hollywood is the proverbial Dream Factory

From an anthropological perspective, cinematic monsters are invaluable. Schatz writes that ‘movies are made by filmmakers, whereas genres are “made” by the collective response of the mass audience,’ (1981:264). Films recreate social persuasions in the form of myths that have a greater existence outside the films themselves (Mayne 1976). Monsters in cinema represent the broad spectrum of threats to the ongoing survival of industrial enlightenment. In the vanquishing of each monster, we may perceive the supremacy of mankind; the technological, cultural and ideological framework of our modern life is re-established and endorsed.

One of the first notable movie monsters is the titular Golem in Paul Wegener’s 1915 silent horror film. The film, standing alongside Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) and Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) as a silent German horror classic, follows an antique dealer who uses a 400-year-old golem as a servant. It might be easily argued that The Golem, with its uncomfortable depiction of Jewish culture and deep symbolism, reflects the burgeoning anti-Semitism that was percolating in early 20th Century Germany during the lead up to the Third Reich.

James Whale’s Frankenstein was released in 1931. Along with Browning’s Dracula (1931), it spawned the Universal Classic Monsters franchise – notable additions include The Mummy, The Wolf Man and The Invisible Man – the legacy of which is so strong that as recently as a few years ago Universal Pictures tried (and failed, strikingly) to ignite a fresh franchise of interconnected narratives revolving around these intellectual properties. In Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818), Dr. Victor Frankenstein’s monster has no name. It is referred to alternatively as ‘fiend’, ‘creature’, ‘daemon’, ‘wretch’ and ‘monster’ (Baldick 1987). That the creature is never conclusively denominated indicates the uneasy line it occupies between humanity and monstrosity. This is an early indication of film’s preoccupation with the uneasy connection between man and monster. Carroll writes that monsters are ‘of either a supernatural or sci-fi origin,’ (1990: 15) and, consequently, cannot be human. But cinema has repeatedly tested this perspective, probing the humanity in its monsters.

Erle and Hendry suggest that though Frankenstein’s Monster may not resemble the good doctor the two are nonetheless connected (2020). Progressive readings of Whale’s film describe the monster as a sympathetic figure. The monster, once alive, occupies the film’s central point of view and is positioned as an archetypal outsider, the latter of which lends the film a strong anti-authoritarian air. Additionally, the monster is dressed in a manner that suggests the working class, establishing him as a clear opponent of traditional authoritative institutions – assuredly a sore point two years into the Great Depression. Whale’s sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) was released only four years later, but revisionist attitudes were already developing toward the notion of the cinematic monster. The film, hailed by many critics as the definitive contribution to monster movies (Young 1991), refracted our social anxieties about race, gender and sex while further humanising the monster by coupling him with the eponymous bride.

King Kong (1933) is also a product of its time, socially speaking. We may observe that a thorough structural analysis of King Kong reveals the seminal RKO monster flick to be a parable for the Great Depression, the monster ultimately defeated by the organised might of technological industry. Mayne writes that the appeal of King Kong ‘to a `1933 audience, plunged in the worst hardships of the Depression years, is most certainly an ideological appeal; and one that must be calculated not according to some vaguely defined notion of fantasy or escape, but rather in terms of the imaginary resolution of social and economic problems that it provides,’ (1976:373).

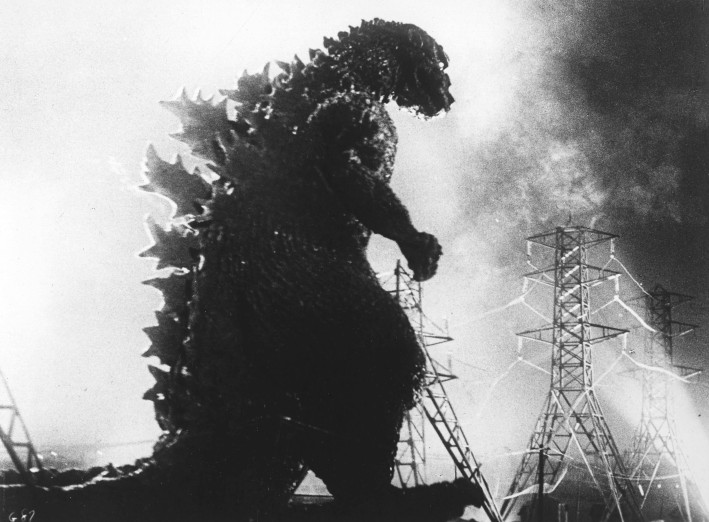

Monsters got bigger with time. The mighty Kong’s Japanese cousin is Godzilla (1954), a response to the unparallel loss and devastation of the fallout of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When the famous giant lizard, depicted in the film as having been provoked by a hydrogen bomb, first premiered in Japan, many audience members were reported to have fled the cinema in tears, so fresh was the memory of the desolation wrecked by Truman’s weaponry. Tellingly, American audiences had the opposite reaction, finding a lot of humour in what they took for simply a tacky monster flick. Keen 21st Century filmgoers will have noted that Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Pictures have been more successful with their recent onslaught of Godzilla and King Kong films than Universal were with their ill-fated ‘Dark Universe’. In the age of the escalating threat of global warming, the pertinence of the giant, city-razing monsters has returned.

For a time after the 1950s, monster movies waned in popularity. Steven Spielberg returned the monster to the forefront of filmgoers’ minds in 1975 with Jaws, the film that almost single-handedly spawned the framework for the modern blockbuster. Jaws, a film that embraces classical monster film tropes at the same time as rejecting them, would announce Spielberg onto the world stage. The fake shark would famously not work on set, causing Spielberg to improvise and reduce the amount we see the monster, to chilling effect. Less than 20 years later, Spielberg would help usher in the modern era of computer-generated cinematic monsters with his technically ground-breaking Jurassic Park (1993).

The technology of cinema is in a constant state of evolution. Perhaps best bridging the gap between classical and modern is John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London (1981). Upon enquiring whether the celebrated transformation scene might be achieved with computer imagery, Landis was informed that the technology wasn’t good enough. “Soon, soon”, was the answer (Landis 2011). Landis’ efforts, along with the efforts of make-up artist Rick Baker, were ultimately so good that Michael Jackson hired Landis and Baker to work on the famous ‘Thriller’ music video. An American Werewolf in London also represents a transition in ideologies of monster movies: the monster was a logical continuation of Lon Chaney’s Wolf Man, the film’s attitudes toward the monster movie far more advanced than in George Waggner’s 1941 classic.

Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986) blurred the distinction between man and monster further, literally fusing its protagonist, Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), with an insect, forming a hybrid monster. Hansen writes that if ‘a human being is the antagonist, or the horror is more psychologically driven, the story or film falls into a different genre rather than that of horror,’ (2012:1) and of course, our definition of what constitutes a monster here is limited. Might Nurse Ratched from Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Henry from Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer or even HAL900 from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey be considered monsters? Monstrous, surely. The distinction between these characters and Frankenstein or The Creature from the Black Lagoon is arguably only cosmetic. Filmmakers in the later part of the 20th Century were more explicit with their examination of the human in the monster; John Carpenter’s Michael Myers in Halloween (1978) or Rob Reiner’s Annie Wilks in Misery (1990). What emerges as clear, regardless of how specifically you might define a monster, is that monstrous figures consistently symbolise some sort of method of dodging genuine implications of the fickle discomforts that arise as a result of the capricious political, economic, social and moral circumstances of our varied cultures.

The case could be made that all of Bong Joon Ho’s works revolve around monsters. Films such as Memories of Murder (2003), Mother (2009) and the recent critical darling Parasite (2019) examine monstrosity on more oblique terms. But Bong continues the illustrious tradition of cinematic monsters reflecting inherently human anxieties and foibles. In Snowpiercer (2013), it is the conceptual leviathan of capitalism that threatens to destroy from both within and without (Ehrlich 2017). In The Host (2006), the monster is literal: the monster is a monster, reportedly modelled by Bong and his team after Steve Buscemi’s slimy performance in the 1996 Coen Brothers film Fargo (Lai 2007). Indeed, Lai suggests that Bong pays homage to Frankenstein in its ‘construction of a subversive discourse that involves politics, class struggle, ecological catastrophe and disease,’ (2007:132). These issues combine in the form of the monster, who reflects communal anxiety as well as individual angst. Bong took advantage of the increasingly affordable digital technology to comment on the political and social uncertainty in South Korea, still processing the repercussions of its most recent war.

In contemporary cinema, the monster spans a wide breadth of production sizes. Modern computer technology means that independently produced monster films with small budgets such as Gareth Edwards’ Monsters (2010) and Nacho Vigalondo’s Colossal (2016) can get made. Auteur filmmakers such as Guillermo Del Toro and Bong Joon Ho are receiving critical acclaim for their original monster films. Originality in blockbuster monster films is a thing of the past. For decades now, large-budget monsters are almost solely rehashes of existing properties, indicating that the monsters we have always known and loved will be known and loved well into the future.

The monster exists on a fundamentally paradoxical level, concurrently inviting repulsion and fear at the same time as they captivate with their odd magnetism. Our fascination with monsters is ever enduring. Mary Shelley’s unnatural creation was dubbed a ‘new species’ by its overextended creator Victor Frankenstein (1818) and the lasting impact of Shelley’s novel extends across a profusion of genres. But though Frankenstein saw his creation as something new, the anxieties of the Homosapien are reflected back at us through the aberrations (Punter & Byron 2004) we commit to celluloid, sometimes representing evil, sometimes moral transgression, sometimes societal failure. This limited use however has evolved over time. The monster in contemporary film culture is a more malleable tool. It can be resilient, noble, powerful and creative. An encounter with a monster can lead to reflection, not just fear, on our attitudes towards society, technology, industry and sometimes even our own bodies.

John Roebuck is the founder and former director of the ReelGood Film Festival, an independent short film festival based at the Lido Cinemas in Hawthorn. The festival, now in its 9th year, champions Australian independent filmmakers. He is the former Editor-in-Chief at ReelGood.com.au, the Melbourne-based film news and reviews website, and has also written for a variety of publications including: The New Daily, Portable, FilmInk, Bunjil Place and STACK.

References

Baldick Chris 1987 In Frankenstein’s Shadow : myth, monstrosity and nineteenth century writing. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Carroll Noel 1990 The Philosophy of Horror or Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge

Ehrlich David 2017 Bong Joon-Ho’s ‘The Host’ is the Defining Monster Movie of the 21st Century, IndieWire <https://www.indiewire.com/2017/05/bong-joon-ho-the-host-best-monster-movie-21st-century-korea-song-kang-ho-bae-doona-trump-1201813051/>

Gamwell Lynn 2000 Dreams 1900-2000: Science, Art and the Unconscious Mind, Claremont: Cornell University Press

Hansen Michelle 2012 Monsters in our Midst: An Examination of Human Monstrosity in Fiction and Film of the United States, UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones, Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press

Lai Christine 2007 Monstrosity as Metaphor: Bong Joon Ho’s The Host, MoveableType – From Memory to Event Vol 3

Landis John 2011 Monsters in the Movies: 100 Years of Cinematic Nightmares. London: DK

Mayne Judith 1976 King Kong and the ideology of spectacle, Quarterly Review of Film Studies, Vol 1 Iss 4

Punter David & Byron Glennis 2004 The Gothic. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Schatz Thomas 1981 Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking and the Studio System. New York: Random House

Sharot Steven 2015 Dreams: Surrealism and Popular American Cinema, Canadian Journal of Film Studies Vol. 24 No. 1

Young Elizabeth 1991 Here Comes the Bride: Wedding Gender and Race in “Bride of Frankenstein”, Feminist Studies Vol. 17 No.3